Before light-up shoes became a staple of sportswear and street style, one British inventor was quietly pioneering the technology that would electrify sneakers for decades to come. John Mott’s journey began in the late 1980s at a technical show in Birmingham, where a flexible piezoelectric film sparked an idea that would forever change footwear. From experimenting with glowing prototypes to navigating the skepticism of global sports brands, Mott’s story is one of ingenuity, persistence, and a vision far ahead of its time. Despite early rejections from the likes of Nike, Reebok, and adidas, his breakthrough with ASICS ultimately set the stage for a new era in athletic footwear, and yet, his name remains largely unknown. This is the story of the man whose shoes shined before anyone else did. View the auction (HERE)

The light-up shoe was something that came to you through running technology. What was the initial idea that sparked it?

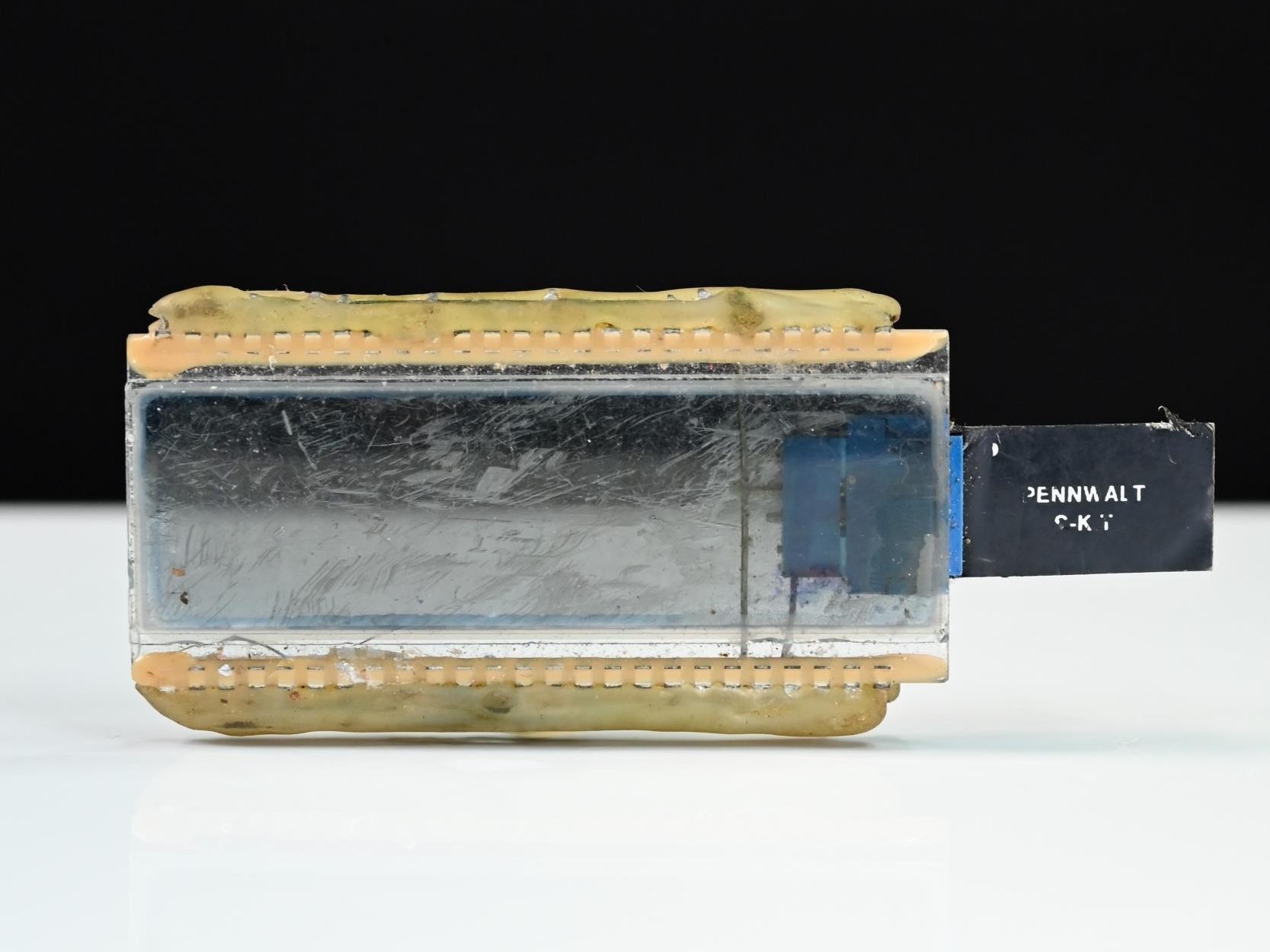

Well, it all started when I went to an engineering and technical show at the NEC in Birmingham, back in the late 1980s. There was a company called Penwalt who had this fascinating material on their stand called piezo film. Most people know piezo crystals, you find them in things like oven lighters, they generate the spark. But this was different: they had turned it into a flexible film. On their stand, they had a demo, a thin piece of grey, silvered plastic with a little neon bulb attached. When you shook the film, the bulb lit up. Even just flicking it produced light. It was incredibly sensitive, the ultimate sensor for detecting not just movement, but pressure.

The moment I saw it, I immediately thought of dynamic signature verification. Imagine embedding this film in a grid, like inside a credit card. If you wrote your signature across it, the system could measure where you started, how fast you moved, the pressure you applied, everything. It could even account for variations, like if you were drunk, and still verify authenticity. That’s how sensitive it was…

Because the film could light things up, the obvious next step was to explore what we could illuminate. I’d always been interested in shoes and sport, so the idea of putting this into footwear was a no-brainer. Of course, when patents are involved, “obvious” can’t really apply, it has to be original. But that’s how the journey began. I worked with a fantastic company in the Midlands called Smallfry. They handled the design work for the shoes, as well as some of my other concepts, rackets, golf clubs, and so on. All beautifully hand-painted, really special pieces. That’s how the first light-up shoe designs were born.

Once you had that initial spark, how did the process of developing it into a prototype actually work? Did you have to purchase the technology or strike a deal?

Having an inventing background helped. Once I started talking with the Penwalt team, they could see I had a clear vision and the drive to make it happen. That’s half the battle, finding people you can actually collaborate with. After a short discussion, I asked them to make a shoe sensor for me. They did, and it worked beautifully right away. One of those early units is still around today. Although there’s a small lithium battery inside, the piezo itself essentially lasts forever, making it very safe. I always warned people not to copy the design with mercury switches, which, unfortunately, some did later on. But the real challenge wasn’t just making it work once; it was about making it reliable, durable, and foolproof.

Compared to some of my other projects, like seven years of work on injection-moulding carbon fibre, creating a working shoe was relatively straightforward. Once we had the durability and consistency nailed down, I was ready to take it further. That’s what eventually led me to ASICS, but I’ll come to that part of the journey when we reach it.

So you have this kinetic film, the impact device. You’ve got a sample and you’re figuring out how it all fits together. What was it like speaking to brands about it?

Honestly, I thought it would be a piece of cake. You take the shoe, you hit it, and it lights up. What’s not to like? There were some surreal moments along the way. I assumed every brand would leap at this. I flew out to meet Phil Knight at Nike. He knew I was coming, but when I arrived, he wasn’t available. Instead, he sent out his vice president, who took the shoe away for a while, came back, and told me it wasn’t for them. I was stunned. I thought it was the most obvious winner of an idea.

I tried Reebok, adidas, Puma, even Clarks in the UK, and they all turned it down. Out of my 85 patents, 84 have been picked up in America. Only one in the UK. That still breaks my heart. It wasn’t until I went back to the US, to one of the big sports shows, that I finally connected with ASICS. I’d known their shoes for years, back when they were Onitsuka Tiger. They were such a breath of fresh air compared to what we had in the UK at the time.

So when I arrived at their stand, I knew it was the right place. Although, like so many trade shows, I still couldn’t understand why it was always such a struggle to actually show people inventions face to face. A lot of brands would flat-out say, “No inventors.” Which I always thought was crazy. That inventor could have the next breakthrough, and if their competitors get it, they’ll be the ones who go bust.

At this point I was so frustrated with constant rejections that I took a bit of a risk. I had a prototype shoe with me, the same one that’ll be the first auction item. Their stand also had a “no inventors” sign, and I’d had enough. So I pulled the shoe out and banged it on the desk. In pure serendipity: a man named Mitch Brabson happened to walk past the glass window of the reception area at that exact moment. He saw the shoe light up, stopped in his tracks, and did a double take. He asked me to do it again. I hit it again, the shoe lit up, and he said, “Don’t go.” Mitch went straight to Peter Gehrig, the president of ASICS USA, and brought him over. He took one look and the rest is history.

How long did it take from that initial spark to ASICS actually taking it on?

The process was between 12 and 24 months. I genuinely thought I had the best thing since sliced bread and as it turned out, I did. But when you’ve had every other brand turning you down, it makes you second-guess yourself. I sold it lock, stock and barrel. Normally I’d aim for a licensing deal, but after so many refusals, when ASICS made an offer, I took it. Inventing is an expensive hobby, prototyping alone cost me about £13,000 back then, which was a lot of money. Add on all the travel costs, and it made sense to accept.

Asics were fantastic to work with. I’ve got lots of great memories, including meeting Mr. Onitsuka himself. He was a lovely man, very small in stature, sadly long gone now, but he made a big impression on me. One time, during an ASICS promo tour, I was on a Denver radio show when two huge New York policemen walked in. I thought they were there to arrest me, but they actually wanted to thank me. Turns out, someone had stolen a pair of light-up ASICS, swapped them into a box, and walked off wearing them without realizing. Later, the police spotted him strolling down Fifth Avenue, glowing shoes and all. They said it made their job “too easy.”

So over the years, your light-up shoe went from an invention to almost an everyday technology. Did you expect it to have that kind of impact?

I always thought it would. In fact, I believe today it’s the second-best-selling shoe of all time behind Nike Air. And there are more things in the pipeline, like model 15A, which you’ll be talking about later. I always believed in it. I was just thrilled that ASICS took it on, they’re such technical, thoughtful people. Mostly I worked with the US team in Los Angeles, but they also flew me to Japan, Korea, and China to sort out factories. Then I toured America, going on radio and TV stations to promote it.

You’ve also worked with Nike on the Air Max 90 prototype, and with Reebok. What was the most difficult challenge when working with those silhouettes?

Those weren’t commissions from Nike or Reebok. They were just shoes I happened to have on hand. I’d take different models, experiment with them, and bring them along to presentations, not knowing who I’d end up talking to. Some of those shoes, like the Air Max, had EVA foam midsoles that crumbled over time. Sometimes I’d pull them off the shelf just to demonstrate an idea, like wiring fibre optics into a Nike sole. When you invent something, your patent agent will actually tell you: “Now knock it off. Copy your own idea.” The reason is, if you don’t, someone else will. So you start experimenting, fibre optics, water, different materials, and each variation makes your patent stronger.

For example, this shoe here is the very first commercial light-up shoe ever made. It even appeared on BBC’s Tomorrow’s World, which, for an inventor at the time, was the programme to be on. The biggest patent challenge we faced was that someone in America had literally strapped a torch to a shoe and called it a “light shoe.” That caused all sorts of problems in the application process. But we got through it, and this ended up being the first true light-up shoe.

When developing the Nike shoe, I did find it a little more difficult to run the fibre optics through the sole, even with all the technology packed in the back. Honestly, a lot of shoes are built on the same basic principle: an upper, a sole, and some kind of cushioning system, gel, air, or foam. Our process was straightforward: we’d take a bandsaw, cut the shoe open, fit the components, and then stitch it back together. It wasn’t rocket science, though I sometimes like to make it sound more complicated. The real breakthrough was the pressure pad, the piezo film, which, in my eyes, was the eighth wonder of the world and still is.

Besides footwear, you’ve worked on many technologies like graphite carbon fiber, which is used in lots of industries now. What was it like working on these inventions?

Let me tell you a little about carbon fibre, or graphite, as they call it in the States. Originally it was aerospace technology, incredibly expensive. At the time, I was making aluminium tennis rackets, which were already outperforming wooden rackets. Wood was out, aluminium was in. Then I came across carbon fibre. I’m not a scientist, but I could see how strong it was relative to its weight, and I thought: this is the future.

I had an idea to braid it. Traditionally, carbon fibre was always made in sheet form, and still is, for most rackets today. They lay the sheets at different angles, add epoxy resin, and then mould it into shape for whatever they’re making: car bodies, rackets, golf clubs. The process is messy and expensive. It goes into an autoclave (a giant oven) and when you close the mould, you get a split line where resin oozes out. Once it’s cured, they slice off the excess with a blade.

But nobody was braiding. And braiding, if you think about it, is like a shoelace, interwoven into a tube. So I went to a company in Holland and asked if they could braid carbon fibre. They could. That’s a lovely long story in itself. We were way ahead of the game. I spent over four years working on it, fascinated by the possibilities. I’ve been lucky with some of my inventions, and I invested a lot of money into this one because I believed in it so strongly.

There’s a company called ICI that invented a resin called methyl methacrylate resin (MMA). If you mixed it together, it was thermoreactive. We found a way to mix it properly, designed a machine to handle it, and then we could take our tubular braided fibres, put them in a mould, close it, inject the resin, and 45 seconds later, bang,it was done. Now, you’ll see what’s called a castellated system, sorry, we can’t show you now, but on September 5th, you can see it all. I used a castellated system, like the up-and-down pattern of a castle wall, by embedding a titanium wire with the same castellated pattern inside the carbon fibre. This effectively eliminated all the holes

Did you see Medvedev yesterday hitting his racket down at the US Open? He lost his temper and got fined $43,000, which was apparently a third of his appearance money. You’ll see that I’m working on a racket that you literally can’t break, it was made in 45 seconds. Even today, there’s nothing like it. Hamish has seen it, and you’ll see some of that technology soon. It’s a fascinating story, but I’ll tell more another day.

Your now auctioning off a decade’s worth of prototypes, including that first light-up shoe. Why is now the right moment to share the collection?

I was married to the most beautiful woman, and together we raised six children. I’ve always been able to speak with confidence, but I’ve never sought publicity. The world has changed though, especially with the internet, and at some point I asked my wife what we should do with our assets. On her deathbed, she gave me the answer: “Why don’t we do what J.M. Barrie did for Peter Pan and give the rights to Great Ormond Street Hospital?” That’s exactly what’s happening now, alongside support for cancer charities and others. You can read all the details in the sales document.

So why now? Because of her. After she passed, I felt it was time to share this story. Not long after, I met Hamish, who lives just two miles away, and he told me it was the biggest shoe story he’d ever seen. That sealed it, it was the right moment to finally speak to the world.

This also ties into something bigger I’ve been thinking about: Great Britain itself. We’ve been selling off our assets, North Sea oil, City money, and watching wealth flow abroad. But the true value of this country has always been its inventors. The British, and particularly the Scots per capita, have produced some of the greatest inventions in the world. When I was a boy, four dollars equaled one pound. Now it’s closer to $1.25. Why? Because we stopped exporting.

We still invent, but we don’t always build. For years, people insisted we weren’t a manufacturing nation, which wasn’t true at the time, though now it’s sadly become reality. Look at Dyson: he wanted to expand in Wiltshire, but the council blocked him after negotiations failed, so he went to Singapore. Once upon a time, we made things here, created jobs, exported products, and built national wealth. We had it all. But slowly it flipped. Out of my own 85 inventions, 84 ended up in America. They kept the jobs, and we bought them back as imports. We had the ideas, but we lost the returns. Leadership failures are part of the story, but that’s another conversation.

Still, I think now is the right time to talk about this. Britain was always known for innovation, for bold ideas that changed the world. Yet today many head offices have left the UK, and the sense of pride in invention seems diminished. That’s why it’s crucial to inspire younger generations. Too often they think everything has already been done, that invention is only for computers, AI, or high-tech labs. But that’s simply not true. New creations are happening every day; they’re just less visible.

We used to have exhibitions and forums where inventors could proudly showcase their work. That culture has faded, replaced by doubt. People say to me, “Surely everything’s already been invented?” I always reply, “You must be joking, we’re only at the beginning.” Take computers: we’ve barely turned the first page. With AI, with medicine, with new tools, breakthroughs are accelerating. The next wave of inventors is already finding ways to push the boundaries. Experience can’t be faked, and if there’s one thing my journey shows, it’s that invention is still alive, still urgent, and still worth fighting.

Lot 1 is the original Light Shoe prototype, but there’s a lot of intrigue around the secret Lots 15A and 15B. Without giving too much away, what can you tell us anything about these “revolutionary” pieces?

Now, about the auction: lot one is the original Light Shoe prototype, which has generated a lot of intrigue. Lots 15a and 15b are even more mysterious. I can’t reveal exactly what they are, but I can explain why I’ve done it. At 74, I’ve realised the world has changed, traveling isn’t necessary anymore, and making shoes, for example, is far easier than it was in my day. Anyway, I don’t want to travel anymore. I’ve got too much going on, six kids, thirteen grandchildren, and I’m not getting any younger.

I thought these two incredible shoe inventions should go out there, so I suggested to Hamish and the auctioneers that we put them in bags, big Mott bags, which have his 4 letter inverted palindromic logo, so people could bid blind. The idea is simple: nobody risks any money upfront. You bid without knowing exactly what’s inside, only that it’s shoe-related and innovative. The purpose of the auction and sharing these inventions is clear: it’s about giving back, inspiring others, and showing that creativity and innovation are still alive. So, 15a… why now? I’m fed up with traveling all over the world. You’ve got the best thing since the Light Shoe that Phil Knight in Boston turned me down.

I say: any shoe manufacturer would be crazy not to bid. But here’s how it works, you make your bid, hand over no money, then sign a non-disclosure agreement. After that, we Zoom in, I open the bag, and show you what’s inside. If you’re not interested, fine, the second-highest bidder gets a chance. If you like it, it’s yours. Anyone can put their name down on an order book so you know theres interest. Its a win-win!

The result? We’ve essentially created an order book. People can express interest in the very first production shoes, which builds excitement even before anything is manufactured. It’s brilliant marketing, and it costs nothing. I’ve taken two life-changing inventions, put them in bags, and created curiosity, hype, and pre-orders, all from my own initiative. Once it’s yours, you have options: lock it away like a priceless artifact, find a manufacturing license with my help, or even start a small factory. Hamish agreed this is the right process, and the auctioneers were initially nervous, but it quickly became very exciting.

How does the rest of the auction work?

For the first 62 lots, I’ll be providing not just images, but detailed commentary and the full story behind each invention. It’s not just an auction, it’s a window into decades of innovation. Every piece comes with context, so bidders can truly understand what they’re looking at and why it matters. When people ask me how long I’ve held onto these items, the answer is simple: forty years. Four decades of keeping inventions that remain state-of-the-art even today. The carbon fibre, the graphite, the experimental designs, they’re not relics of the past, but technologies still at the forefront of engineering. Seeing them in person, people will quickly grasp just how advanced they were for their time.

By law, there will be a handful of open days near Winchester, giving the public a rare chance to handle these innovations up close. Visitors can take photographs, ask questions, and hear the stories behind the patents, over a pint, if they fancy, since that’s the only cost of entry. The auction method being used here is a timed online auction, which works in a way that’s quite similar to eBay. Instead of bidding in real time with a live auctioneer, participants enter the maximum amount they’re willing to pay for an item. The system then automatically increases their bid incrementally as needed, only going as high as necessary to outbid other participants.

To make the process fairer, the auction has a staggered finish. This means that items don’t all close at once, reducing the risk of people missing out due to timing. On top of that, there’s a five-minute extension rule designed to prevent last-second “bid sniping.” If someone places a bid in the final moments, the auction for that item will stay open for up to five more minutes, giving others the chance to respond rather than losing out instantly.

Sneakers have evolved beyond mere footwear, they’re cultural artifacts, collectibles. How do you think brands and collectors view an auction like this?

Hamish was blown away, not just by the opportunity to be involved, but by the history and the marketing side of things. He’s done all the filming, and when you see this story come to life, you’ll know he’s been behind it. He has tons of marketing ideas; he’s brilliant. When he saw the fiber optics in shoes 2 through seven, he was fascinated, things nobody had ever done before. It’s rare to see an inventor with such a breadth of work. Clive Sinclair had a couple of ideas, Dyson a few, but I have 85, covering an eclectic range. Presenting it like this, in this format, allows people to actually talk to the inventor. If you win a bid, you get half an hour with me on Zoom to discuss whatever you bought. That adds provenance, you’re getting the real deal, signed, with documentation and images.

Hamish : When I first met John, he told me he invented the light-up shoe, and I was floored. There’s so much in sneaker history that’s been rehashed, recycled stories, like with the Air Max line. This is fresh, people have seen light-up shoes in playgrounds, but few know the true origin. Even sneaker historians might incorrectly credit LA Gear. Bringing this unique piece into the world finally sets the record straight. The story was first documented by Woody from Sneaker Freaker back in 2022 in issue 48, but unless you’re a true sneakerhead, you probably missed it. For most, this is a fresh story.

What would you say to inventors starting out today?

Selling has changed, that’s the big thing. Back when I started, everything was painfully slow. Samples had to be sent to stores, who’d then decide whether to place an order. Then you’d wait again, for payment. Small shops, like the little racket stores I worked with, were chaos: they’d pull out your beautiful rackets, knock them about, hand them out as samples, and you’d be left cleaning up the mess. You didn’t need Tesco or Waitrose anymore. With the internet, you can go straight to the customer. They pay upfront, you ship, cash flow is faster, and the process is immediate.

Today, it’s completely different. With 3D printing, you can send a design and have a prototype the next day. Maybe it needs a tweak, but you’ve already cut weeks, sometimes months, off the process. Mass production still relies on injection moulding, but that early testing phase is almost instant. For inventors, it’s never been easier. Mistakes are spotted fast, fixed fast, and improvements happen quickly. Think of it like glass: at first, it’s just a vessel. Then someone adds a handle, and suddenly there are two patents to consider. You learn to make them coexist.

With 3D printing, that “handle”, the Mark II version, can be made almost instantly. Patents? That’s another story. Some people want them, some don’t. Shows like Dragon’s Den entertain, but the reality is different. It gives a glimpse into how the system works, but the real lesson is simple: jump in and try.

Related posts

Never Miss A Drop

Sign up to our free newsletter to keep your finger on the pulse with exclusive content, raffles, releases and so much more!

Upcoming Releases